I am a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Stanford University. I study political theory and comparative politics. My research focuses on social movements in North America with global solidarities and influence, including Prison Industrial Complex Abolition, Hawaiian Sovereignty, and Christian Nationalism.

I am a political theorist on the 2025-2026 job market for positions in Political Science, Philosophy, Women and Gender Studies, and American Studies.

Writing

“Highly Aspirational Political Movements” (Read Paper Here) Many of today’s movements seek extensive restructuring of society. Some such examples include “Land Back,” indigenous peoples’ movements to reclaim sovereignty over unceded territories, or “No Borders,” the movement to abolish state boundaries. These movements are recognizably characterized as radical, revolutionary, or utopian; however, this existing vocabulary obscures the structures and practices that organize the pursuit of far-reaching aims under constraint and over time. In this paper, I develop a theory of movements that seek to change everything, and call them Highly Aspirational Political Movements (HAPMs). HAPMs share three common features that emerge from the political thought of their movements. One, movement members are dependent on the very institutions and ideology they criticize. Their dependence keeps them in a bind in which their attempts for structural transformation are hindered by continuous use of systems they criticize. Two, they rely on imaginative practice like prefigurative experiments and narrative frames to overcome structural dependencies and to convert critiques into actionable strategies for social transformation. Three, movement members have a sense that their movement is operating on a generations-long or even indefinite timeline; they acknowledge the possibility their movement may never succeed, yet they persist. To illustrate the HAPMs theory, I conduct a comparative study of three contemporary North American movements: prison-industrial complex abolition, Hawaiian sovereignty, and Christian nationalism.

“Toward The Abolitionist Ethic: A Black Feminist Ethics of Anti-Carceral Resistance” (Read Paper Here) Over the last decade, Black feminists have published extensively on the prison industrial complex (PIC) abolition movement. Throughout PIC abolitionists’ writings, there is an underdeveloped theme of a personal, relational ethic that those with abolitionist commitments should espouse and practice. The paper systematizes the political ethics of abolitionism and names three distinctive, interactive features of abolitionists’ morality: their political analysis, their adoption of non-punitive intuitions, and their practices of emotional regulation. Until now, there has not been a comprehensive account of what ethical modes abolitionists adopt. In introducing this ethics, I aim to demonstrate how every day ethics can be a meaningful response to the routinized violence of the prison industrial complex. Finally, the paper elevates the normative political theorizing of a particularly anarchistic branch of Black feminists in order to open up avenues of inquiry about ethical political action beyond state structures.

“Self-Transformation for Self-Governance” (email me to request draft) I argue that by linking inner change to enduring structures Kānaka Maoli envision sovereign futures beyond the legacies of militarism and imposed governance. Drawing on personal writings from the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana, especially the journals of George Helm, I develop a theory of self-knowledge as a political practice. I show how intimate relationships, kinship ties, and Hawaiian language revitalization foster the internal capacities required for self-governance. Helm’s reflections on desire, jealousy, and responsibility exemplify how interpersonal work becomes political work. ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, in turn, reorients emotional life toward ʻāina, embedding shared norms and place-based ethics that sustain collective action. Framed within the intergenerational arc of the Hawaiian Renaissance, this aspirational politics demands long-term commitments to self-discipline, strategic clarity, and communal care.

“Cedric Robinson’s Challenge to Political Science” (email me to request talk or elongated abstract) In this paper, I argue that Robinson’s ideas of the charismatic provide rich theoretical ground to transform how social scientists understand social movements and anarchism. (click the tab to see additional details)

I reconstruct Robinson’s thinking from his largely understudied early works: “A Modest Assessment” (1968), “Malcolm Little as a Charismatic Leader” (1972), and his dissertation, “Leadership: a Mythic Paradigm” (1975) which gets republished as Terms of Order (1980). To conclude the paper, I engage Robinson’s Black Marxism (1983) to demonstrate both the liberatory and dominating potential of the charismatic and its anti-political forms.

“The Politics of Personal Transformation” In this paper, I theorize about the relationship between aspirational movements and a politics of personal transformation: What does personal transformation have to do with wide-reaching structural change? (click the tab to see additional details)

Why do some movements view personal transformation as not only instrumental for, but also constitutive of structural change? In answering these questions, I draw theorists into a deep study of a particular strand of personal political ethics that emerges from highly aspirational political movements, and has resonances across historical contexts – Gandhi’s conception of “being the change,” Foucault’s “government of the self,” what Thomas Hansen synthesizes as “belief as practice” and what Feminist Philosophers have described as “the politics of personal transformation” (Foucault 1994, 89; Hansen 2009, 5; Tessman, 2000, 375).

Teaching

I have developed two courses as Instructor of Record at Menlo College, including POLISCI 150: Intro to U.S. Politics and POLISCI 200: Native Hawaiian and Indigenous Politics. Below I’ve included course descriptions and a flyer for the upcoming spring semester class!

POLISCI 150: Intro to U.S. Politics

Course Summary: In this course, we begin to understand various actors, geographic regions, and values that signify “the founding” of the United States’ federal government. We develop a basic understanding of the theoretical differences between the executive, judicial, and congressional branches of government as well as the role of political parties in national agenda setting. To develop an account of how these branches of government have exercised their powers, whether within their theoretical constraints or beyond them, students will have the opportunity to study federal operations within one field of governance: the carceral system. The carceral system refers to the complex of jails, detention facilities, and prisons throughout the United States.

We will move back and forth between theory and history (or practice). Over the course of the semester, we will learn the normative reasons for the designs and functioning of the U.S. federal government, political participation, and American democratic institutions. Every time we are introduced to a new theoretical insight, we will turn to history, geography, and sociology to understand how these normative ideals are challenged by material and cultural conditions. The readings for this course are some of the best works by the most talented researchers, historians, and theorists. These writings, enhanced by our classroom discussions, will help you build a foundation for more advanced Political Science courses. By the end of this course, you should feel prepared to engage in meaningful, varied discussions about the politics of American society.

POLISCI 200: Native Hawaiian and Indigenous Politics

Course Summary: This course explores Indigenous politics through diverse perspectives on sovereignty, belonging, and knowledge. We examine how Indigenous peoples have navigated and contested colonial projects of dispossession while asserting enduring forms of agency and self-determination. Readings and films trace how sovereignty operates not only through formal governance but also in intimate, epistemic, and embodied domains. Topics include the politics of tourism, issues of representation, and alternative epistemologies that challenge the normalizing gaze of the academy. We also study recent Land Back movements and court rulings that have restored Indigenous ownership or stewardship over significant tracts of land, analyzing their implications for federalism, property, and environmental governance. By centering Indigenous voices and political strategies, the course invites students to rethink core concepts of American politics, sovereignty, citizenship, and territory.

I have taught in a wide variety of contexts, in multiple languages with learners of all ages and varieties of life experiences. Please see my CV for additional information about my teaching background.

Specializations and Technique

I take special interest in the political theorizing of Iris Marion Young and Cedric Robinson. These theorists practice historically and socially grounded normative theorizing with a range of emphasis on building theory out of the activity of emancipatory efforts and generating normative conclusions from an outsider’s position.

My political theorizing straddles both analytic and ethnographic techniques. As a Fulbright scholar, I spent a year conducting ethnographic research in various communities in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, moving fluidly between Gujarati and Hindi. The research agenda above emerges out of modes of listening and observing paired with an interest in conceptual clarity.

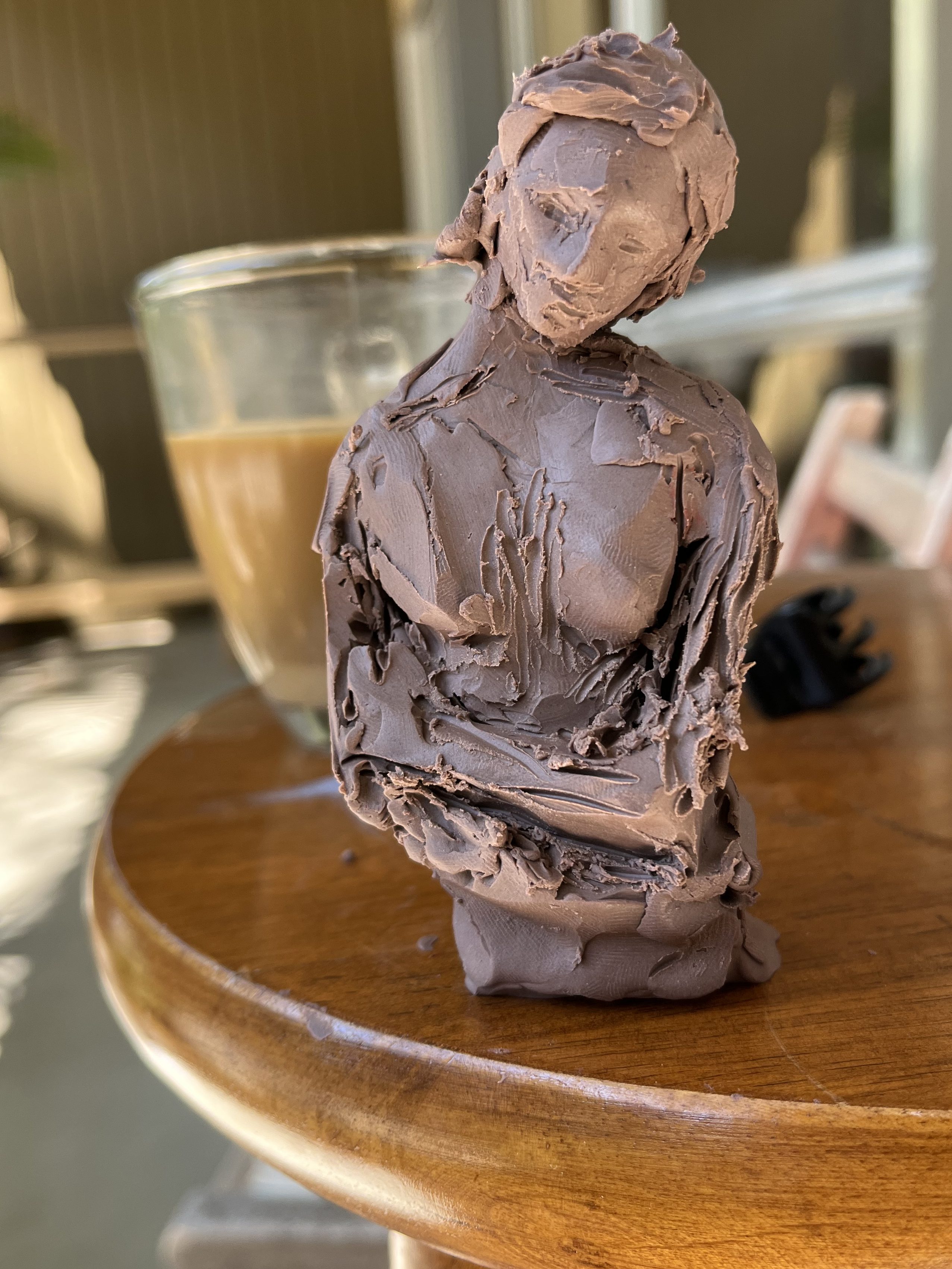

some sculptures

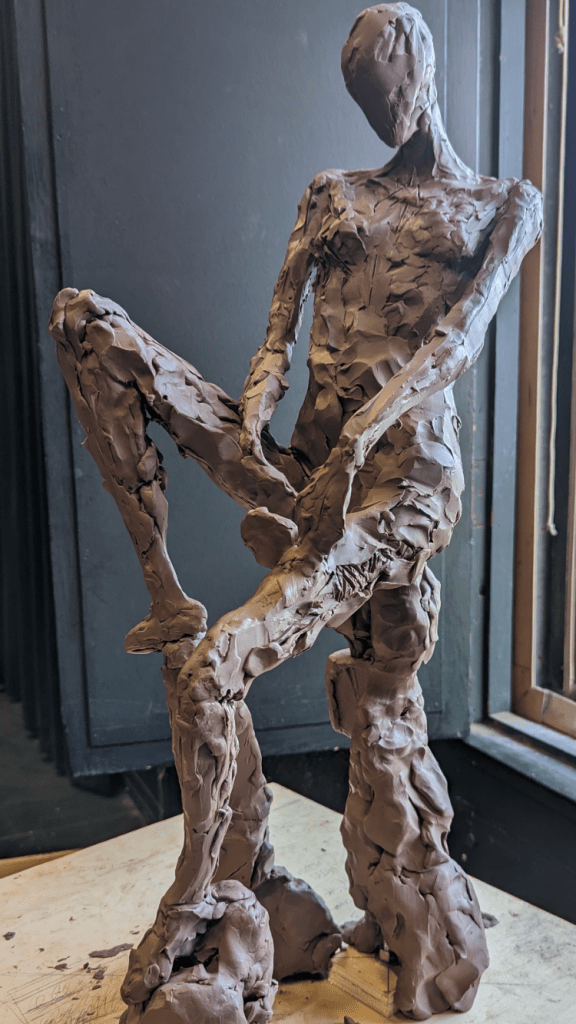

Álida: Healing and Stretching

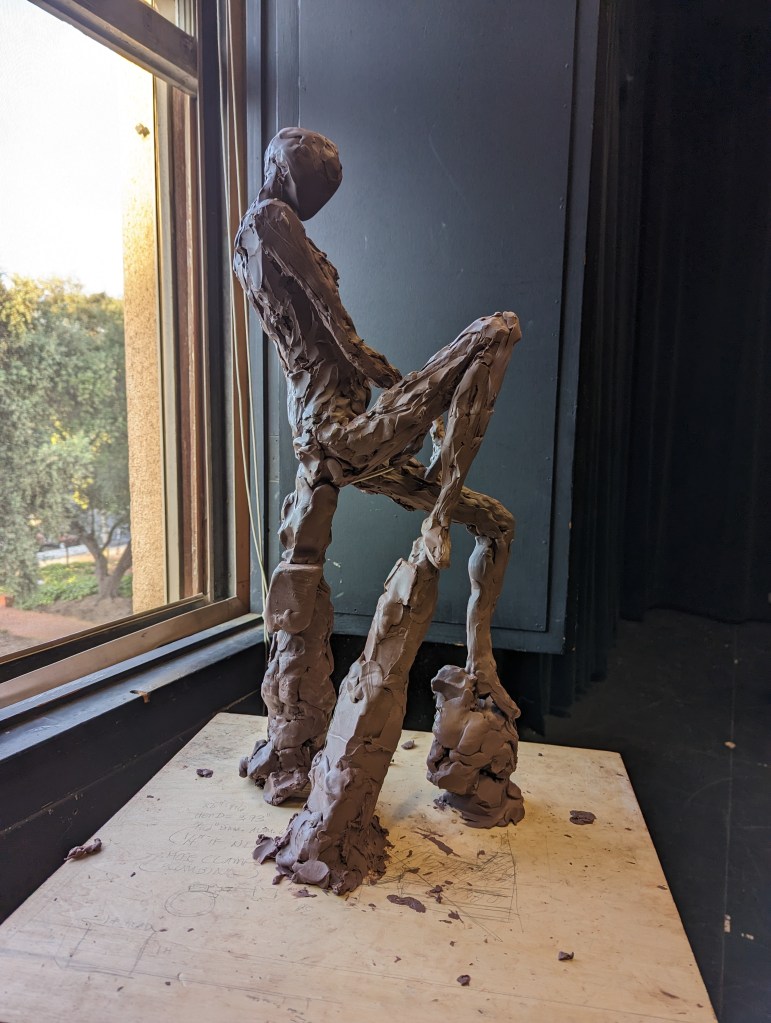

Concussive Syndrome

some paintings

Please write to me if any of my work interests you. I enjoy mentoring, collaborating, and learning from others.